Rules are meant to be broken, or so they say. Even so, writers have a few sacred rules that common sense tells us must be respected for the sake of a sound story. Here are five books that broke those rules, and despite their audacity, won our hearts.

Cinder (The Lunar Chronicles) by Marissa Meyer

Broken Rule: plot based on a tired old fairytale that has been done to death.

Broken Rule: plot based on a tired old fairytale that has been done to death.

I was skeptical. After all, Cinderella, seriously? Been there done that. What could Ms. Meyer possibly do that would be new?

But the cover was so darned intriguing, that after trying not to look inside seven or eight times, I acquiesced and opened to the first chapter. Color me a goner. Cinder is a Asian Cyborg–can you believe it? Not only that, but the talented Ms. Meyer’s paints such vivid characters that I felt as if I’d been sucked into a live action anime.

Brilliant.

She does one more thing that totally amazes me. Each of the next three books in the series bring in a new protagonist, and each is a adaptation of another fairytale. Yet Meyer weaves all these stories together beautifully and keeps the reader connected to the previous characters. When she got to book three, Cress, a Rapunzel-esque heroine, I thought for sure the author would lose her grip on the other story lines. For pity’s sake, Cress is trapped in a satellite. In space. Alone.

But no, Meyer pulled it off with as much magical finesse as David Copperfield sawing himself in half. I can’t wait for Winter to come out. The Lunar Chronicles are one of this decade’s masterpieces.

Jamaica Inn by Daphne du Maurier

Broken Rule(s): non-protagonist points of view and numerous redundancies.

Broken Rule(s): non-protagonist points of view and numerous redundancies.

Most writers compulsively check and double check for echoes and redundancies and remove them. Contrast that with Daphne du Maurier’s, Jamaica Inn. The opening paragraph contains no less than five redundancies and repeated images.

Du Maurier also head-hops, shifting from various points of view, before narrowing to the protagonist. Normally, this is a no-no. But du Maurier eases us deeper and deeper into the story as deftly as a skilled hypnotist puts an audience into a trance. By the end of the first page readers are wiping imaginary rain from their brows and snuggling deeper into their sweaters to stave off the cold. Thus opens the mesmerizing tale of murderous pirates and grey moors. Read it and the images will remain etched in your mind forever.

Du Maurier’s classic mystery Rebecca is equally unforgettable. Here again, you’ll see multiple repetitions in the first paragraph. I suspect Daphne du Maurier figured out how to put her readers under a spell using a form of linguistic hypnosis.

Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones

Broken Rule: meandering plot and uncertain settings.

Broken Rule: meandering plot and uncertain settings.

In Howl’s Moving Castle, half the time the reader isn’t sure where they are, or what they’re doing there. The plot meanders as much as the castle does over the countryside. And yet it is still a compelling story and remains one of my all-time favorites. Diana Wynne Jones, author of more than thirty critically acclaimed books, does not pre-plot. She says, “No, that kills it dead.”

I agree. But here’s what she does do in all her stories, and did masterfully in Howl’s Moving Castle; she fascinates us with unexpected twists and turns and delightful character discoveries. Somehow Jones manages to weave wildly unpredictable plot lines together and produce a tale with a theme revealed at the end.

Reading Jones is like riding a rollercoaster in the pitch dark. Hang on–it will end up in a bright good place.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Broken Rule: multiple regional dialects that are challenging to understand.

Broken Rule: multiple regional dialects that are challenging to understand.

No discussion of writerly rule-breaking would be complete without mentioning Mark Twain and his landmark novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Writers today take our use of regional dialogue for granted, but Twain, and a handful of other authors, blazed the trail for us. Twain broke from the prim and proper literary forms of his day and ripped it up with shockingly realistic dialogue. He didn’t exploit just one regional dialect; he had Aunt Polly’s homespun southern flavor, Huck Finn’s uneducated twang, Pap’s use of onomatopoeia and poetic phrasing, and Jim’s slave lingo.

Twain got some serious grief for his bravado. Newspaper critics weren’t impressed. The public turned up its collective nose. Fortunately, Twain’s novels outlived the criticism. Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn were among the first books my mother read to me as a child and they remain favorites still today.

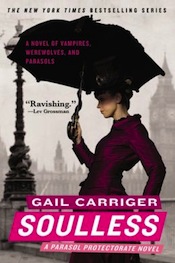

Soulless (The Parasol Protectorate) by Gail Carriger

Broken Rule: the main character’s traits are not universally relatable.

Broken Rule: the main character’s traits are not universally relatable.

In Gail Carriger’s Parasol Protectorate series the main character Miss Alexia Tarabotti was born without a soul. She is completely unflappable. Nothing alarms her. She is not fearful or passionate. Point in case, the story opens with a vampire trying to bite her, but when Alexia subdues the offender and he collapses at her feet she is perturbed, not by his attack, but because he has fallen on a plate of treacle tarts she’d intended to eat.

Penning an emotionless heroine was a gigantic risk. Readers read for vicarious emotional experience. So why did a rule-breaking book like Soulless rocket up the charts?

Chalk it up to Carriger’s top shelf sense of humor. Few writers have her wit and tongue-in-cheek sarcasm. Although her heroine doesn’t feel much, Carriger makes readers feel intelligent as they experience all the spoofy goings-on. It is as if we are in on the grand joke rather than simply observing.

Genius!

Kathleen Baldwin has written several award-winning traditional Regency romances for adults, including Lady Fiasco, winner of Cataromance’s Best Traditional Regency, and Mistaken Kiss, a Holt Medallion Finalist. A School for Unusual Girls is her first book for teens. She lives in Texas with her family.

I don’t know if I agree that Alexia is emotionless. She demonstrates often that she FEELS. She loves Conall, she’s hurt when he doubts her honor, she cherishes Ivy. And her father was a man of many passions. More than anything, she’s supremely PRACTICAL.

I do agree that she’s not universally relatable, however.

A similar character is Loup Garron from Jacqueline Carey’s Santa Olivia. She’s a mutant, genetically engineered to not feel fear. And Carey examines this trait extensively, what she does feel when she should be scared, how not being scared makes her reckless, but also the ways that lack of fear allows her to live a life without embarrassment, because as another character says “you have to be afraid of what people think of you to be embarrassed”. She also inspires others because when they see her act so fearlessly, it helps them realize how their own fear limits themselves.

I really don’t think unlikable characters is a broken rule of writing- if you’re writing characters that are unlikable, they are at least compelling and interesting enough that the reader has an opinion on them. also, character traits aren’t supposed to be universally relatable, because nothing is universally relatable, but I don’t think Alexia Tarabotti is unemotional. she is cool and logical in the face of danger, but she definitely has emotions. she’s not soulless in the way we perceive it in this world, I don’t think, but more that she lacks anything creative or passionate in her personality, which is much different from both our world and also the universe she inhabits. either way, I find her extremely relatable, both as an emotional protagonist, or a cool, logical one.

I have to agree with Aeryl, Alexia is NOT unemotional. She’s just not overly so like most of us.

Agree. Alexia is very much NOT unemotional. :) Interesting post, though.

Maybe being sufficiently emotionlessness is an emotion of its own!

How about Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon?

The rule it breaks? A constant barrage of massive infodumps on very diverse subjects that are sure to bore the hell out of some readers. The book is constantly telling instead of showing.

Why do I love it? He manages to make those infodumps some of the most engaging and interesting stories I’ve ever read.

I would like to point out, as an avid fan of The Parasol Protectorate, that Alexia isn’t emotionless. She might not be relatable, but she is a strong, intelligent, and independent woman who I can look up to. I feel that being able to look up to a character and admiring them is just as important as relating to them. She wasn’t a super emotional character, but she made sure her opinions and feeling were very known.

Alexia is also a character in the tradition of the unflappable Victorian adventuress like Elizabeth Peters’ Amelia Peabody. So, no, I don’t think she’s emotionless either.

There’s also the problem of applying current standards on older traditions or writing techniques. Du Maurier was true to the viewpoint elements of her time as Twain was about dialect in his. He just did it better.

Jones’ HOWLING CASTLE, which I haven’t read, sounds picaresque rather than meandering, and picaresque is as much a plot type as the main character’s focused attempt at reaching a goal so common in most genre now.

I agree with everyone in this thread that Alexia from Soulless is anything but emotionless. To the point that my biggest complaint about the book was how, exactly, were we supposed to know she’s soulless other than her preternatural ability to cancel supernatural abilities? Just because she has a certain aplomb in strange and dangerous situations? Because she’s intelligent? Because she wants more out of life than the other women of her acquaintance?

Good gods, she even allows her family to convince her on a very deep, emotional level that she is worthless. Her confrontations with Conall, and his with her family, about this very issue had me in tears.

Alexia is very emotional.

A book that has an unrelatable protagonist and that I adored from the first paragraph is Empress, or Empress of Mijak in Australia, by Karen Miller. Hekat is a character you really can’t relate to even from the beginning of her story, though you can certainly sympathize with her and hate the conditions she comes from. As the book goes on, however, she becomes ever less likeable. As a reader, it’s easy to see where she goes wrong, and how she might have gone different ways, so it’s hard to hate her, just what she becomes.

Diana Wynne Jones is I am sorry to say dead. It seems the writer is unaware of this. Since she is the only dead author the article refers to in the present tense.

Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination begins with a lecture explaining the book’s New Thing (or one thereof).

I was reminded of Madison Smartt Bell’s novel, Devil’s Dream, based on the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. And if you thought Hilary Mantel had a tough job with Thomas Cromwell…! Forrest made his fortune from slave-trading, was credibly accused of war crimes, went on to be one of the founders of the Ku Klux Klan. Not a nice person, and Bell doesn’t try to make him nice, although he’s sometimes relateable.

Further, the story shifts back and forth in time in a meandering and uncertain fashion, and large parts of it are narrated by someone who turns out to have been killed halfway through the war. That person, the escaped slave Henri, turns out to be the real viewpoint character.

If Wolf Hall is an attempt to show us the world through Cromwell’s eyes, Devil’s Dream is an attempt to show us the world that produced a Nathan Bedford Forrest, without excusing his own complicity in the worst of that world.

I didn’t exactly love the book, but it was interesting.

Two of my very favorite books here — Howl’s Moving Castle and Soulless :). I’ve reread both countless times.

No mention of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy?

Rule broken: the main character has essentially no agency whatsoever.

Rule broken: the plot is only a very minimal cover for the writer’s meandering, inconsistent worldbuilding.

Rule broken: characters are essentially static over the course of 6 books.

Rule broken: …. etc, you get the idea.

Yet it’s an absolutely fabulous book.

The only writing rule is “there are no rules”. There are preferences and tastes and things that have been successful and so are copied. But there is no stone tablet somewhere with “Thou shalt have rising action, climax, then denoument” chiselled on it.

(Nor would I could Howl’s Moving Castle “meandering”. Like much of DWJ’s work, we have a series of events, some of which don’t seem related to each other, which lock together into a finely-chiselled climax where everything turns out to be linked after all.)

Howl’s Moving Castle is like my go-to recommendation for friends who want to try fantasy (or reading in general :P). Everyone loves it!

@16 I don’t agree. There are rules. It’s just that a very talented writer knows how and when to break them. (And you have to know the rules in order to successfully break them.)

MAJOR SPOILER WARNING FOR A FIVE-YEAR-OLD BOOK.

In Feed, Mira Grant (Seanan McGuire) breaks what I think of as a truly fundamental rule: you cannot kill your first-person past-tense sole narrator, especially not several chapters before the end of the book.

It works, and the story has established its stakes by the time this happens, but I really felt like I’d had the rug pulled out from under me the first time I read it.

Harlan Ellison’s short story “”Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman” was written specifically to break every alleged rule of good writing. It became one of the most frequently reprinted English language short stories.

Every now and then I browse the various Teacher’s Websites when there’s a session devoted to how to teach (that is, “explain”) Huckleberry Finn’s often-unpleasant terminology to easily pissed-off or offended or self-righteously-guilty high school students. After lurking a bit on one of those sites I got impatient, unlurked and commented, something like:

“Enough with all this explaining, not enough demonstrating–[teachers, like writing instructors, love show vs. tell analogies]. Get your kids (if your school can pay for it) to concurrently read the heavily n-worded but pro-brotherhood Huck Finn and the daintily un-n-worded but very racist Gone With the Wind. Your kids will figure it all out on their own, without you wasting their time.”

Haven’t heard back.

“Resenting the Hero” by Moira J. Moore has a main character intended to be unemotional, or at least less emotional.

consider toes stepped on by fans of Gail Carriger. lol so many people repeating themselves. Must be a good book, I think I will pick it up.